Fighting for Football in China

Standing on a football pitch in the heart of Beijing, I was assisting my friend Tao with training a youth football team when it suddenly struck me. At that very moment I started imagining the different stories of these kids as a powerful visual idea and a side of China very few people get the chance to see. Since my first visit to China in 2006, I have struggled with sharing my experiences with friends, family and even business associates because somehow I felt that they did not fit the usual western opinion about China. That football pitch profoundly changed my life, as only four months later, I quit my job in banking to pursue this idea and make a documentary about what I had observed that day.

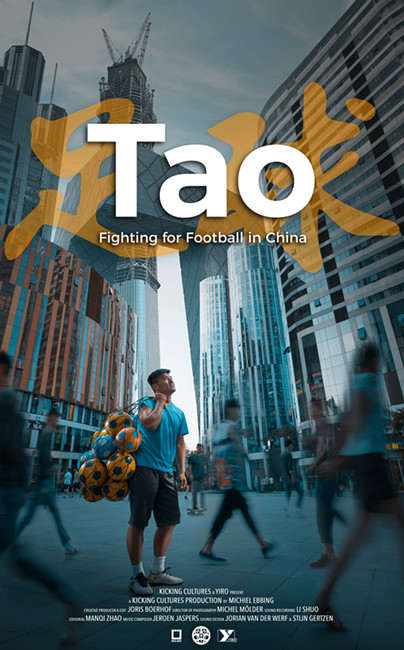

- Poster of the documentary Tao: Fighting for Football in China ©Michiel Ebbing

Who knew that going to Beijing in 2006 to study Chinese would trigger such a life-changing experience. China, I first thought, is chaos. So radically different: huge, fast-paced, diverse, but above all, extremely different. I still find it hard to make sense of it all, but the longer I stayed, the more I enjoyed the chaos. I got such a thrill from the many unexpected surprises and encounters, and how reality clashed with my assumptions. Being in China made me question everything I knew and believed in. That first Chinese trip inspired deep self-reflection for which I will always be grateful.

I became a documentary filmmaker without any prior experience or skills in that field whatsoever. Not because I loved documentaries or hated banking, but because I felt there was a story to tell. I was perhaps not the most qualified or talented story-teller, but no one else was telling this story. China is still misunderstood in the West in my view, and it’s not because people lack interest. Since my first encounter with Chinese culture twelve years ago, the fascination for China has increased steadily, while inaccurate notions about Chinese culture persist. In addition to the lack of diversity in media coverage, language and cultural barriers, as well as internet limitations in China might also be factors affecting people’s opinion.

So what could I do about it? I cannot change Chinese internet policy, or the language, nor can I influence how media organizations portray Chinese culture. Or could I? Never have I felt the urge to become a journalist or the need to get my voice heard publicly. I certainly do not pretend to have all the answers and my opinion to be the only truth. However, I realized that personal observations are exactly what is missing in the current media spectrum. Independent voices without any affiliation to media companies, investors, or government are not heard yet. I decided it was time for me to share mine to show the China I got to know through its people. With a camera and a vision I embarked upon this documentary journey to present a story told by Chinese people.

- Shooting the documentary ©Michiel Ebbing

Football is considered one of the most popular sports globally. Until recently, not many people knew that it is quite popular in China as well. The earliest form of football recognised by FIFA is an ancient ‘kickball’ game that originated during the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) in China, which was called “cuju”. In more recent times, football has also received serious interest from China's renowned leaders. Mao Zedong had played as a goalkeeper in his early 20s, Deng Xiaoping had sought to improve the level of Chinese football and the current Chinese President Xi Jinping has vowed to bring the sport to a whole new professional and international level to improve its world ranking. In 2015, the Chinese government announced an ambitious football reform plan, with the goal to become a world football superpower, which could one day host the World Cup. The reform involves establishing 50,000 football schools by 2025 to be overseen by the Ministry of Education. This was a necessary measure because sports were seen as a distraction to education. Although China has caught up in many sports on the elite level, sports are not yet part of daily life for most Chinese children. Many parents are unwilling to let their children spend precious time on sports activities rather than studying for their biggest challenge: the Gaokao. This is China’s national college entrance examination, which can determine students’ future and impact the livelihood of their family. The competition is fierce and could partly explain the empty football pitches. But that is changing, since youth football has been booming all over China as part of the so-called “campus football” in the reform.

In our documentary we follow Tao, a football trainer from Beijing, whose dream was to set up his own football club in the capital. He graduated from a top Chinese university fifteen years ago, in which he had been admitted with a football scholarship. He was about to start his football career, landing a position at the training camp of a professional club. This is when he hit rock bottom, losing his love for the sport. Back then, Chinese football was in shambles. Bribed referees, corruption, and rigged matches overshadowed the game, and Tao decided he wanted no part in it ever again. He became an English teacher and started working with children. More than ten years later, the parents of his students learned that he used to be a professionally trained football player and convinced him to start teaching their kids football. This is when he set up the Beijing Magpies Football Club, just months after the government had announced its football reform. A guarantee for success, it seemed. But the reality turned out quite differently.

Tao ran into all sorts of difficulties, akin to the obstacles and challenges Beijing society is facing today. Economic developments since the Great Leap Forward have brought tremendous wealth and prosperity to the country, but also new problems. Severe pollution is a serious threat to people’s health in Beijing. On many days it is even healthier to stay indoors rather than to practice sports outdoors. Furthermore, overweight and obesity have become an increasing health problem in China due to changing dietary habits and a more sedentary lifestyle. Culturally, sports are not part of everyday life yet. But recent initiatives from the government, including the football reform are meant to include more sports within the physical education syllabus in schools.

In the documentary we also follow two boys, Sam and Peter, who love playing football, but it’s just one of many extra classes they must attend. English, math, robotics, music, calligraphy, dancing, painting, and fencing are all part of their weekly schedule. There is simply not much extra time for another sport, although during weekends more parents are convinced of the positive effects of football on their children. This in turn creates a new problem: the limited availability of pitches during weekends. Beijing has over 20 million inhabitants who all need a place to live, go to school, work, eat, and now also play football. There is very limited space for football pitches. When Tao finally gets to reserve one for his training, the pitch manager can choose to rent it out the following week to a higher bidder.

- A scene in the documentary ©Michiel Ebbing

Changing the face of Chinese football is an incredibly complex task for the government, let alone for one football coach. Although the government’s reform underlines its determination to develop the football industry, creating an environment that can stimulate grassroots football development is turning out more challenging than anticipated. While many are looking for national football success and glory, Tao is just focused on sharing his passion for the game and helping children find their way in modern Chinese society. They don’t have to become the next Messi or Cristiano Ronaldo. Having fun is what’s important.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn