Chinese Foreign Language Teaching and Learning in the Netherlands

Chinese Foreign Language (CFL) Teaching is a subject area that has fascinated me for some time. It combines my professional pursuit as a language teacher as well as my passion for conveying the Chinese language and culture to people from other countries. Following my sustained interest in linguistics and education, I started my doctoral journey, focusing on Chinese foreign language teaching in an intercultural context, at ICLON, Leiden University in the Netherlands. Living and studying in the Netherlands gives me a chance to explore the questions I am intrigued by. How is the development of CFL education in an overseas setting, such as in the Netherlands? What is the current situation of CFL education in the Netherlands? What opportunities and challenges does CFL teaching and learning face in the Netherlands? This article will share some highlights from my Ph.D. studies, aiming to provide an overview of CFL education in an intercultural context in the Netherlands.

Chinese Foreign Language (CFL) Education in the Netherlands

The History of CFL Education in the Netherlands

The Chinese community in the Netherlands can be traced back to 1918 when the early Chinese immigrants―peddlers and seamen―made the Netherlands their home. Since then, Chinatowns have emerged, particularly in the urban centers of Rotterdam and Amsterdam. In the 1930s, the first Chinese schools were established in Chinatown, teaching Chinese language and culture among a range of core subjects to its attendees. In the almost 100 years since the establishment of the first Chinese schools, Chinese foreign language education has made a breakthrough into the Dutch education system. A special fund was invested by Dutch Culture and Welfare Ministry to support Chinese education and develop Chinese textbooks suitable for the Netherlands in the 1990s. The Chinese language now features an elective course in secondary schools, where it has been offered as a centrally assessed exam subject since 2007. It is also delivered as a foreign language in the higher education in the Netherlands, in Groningen, Leiden and Maastricht.

The Current Situation of CFL Education in the Netherlands

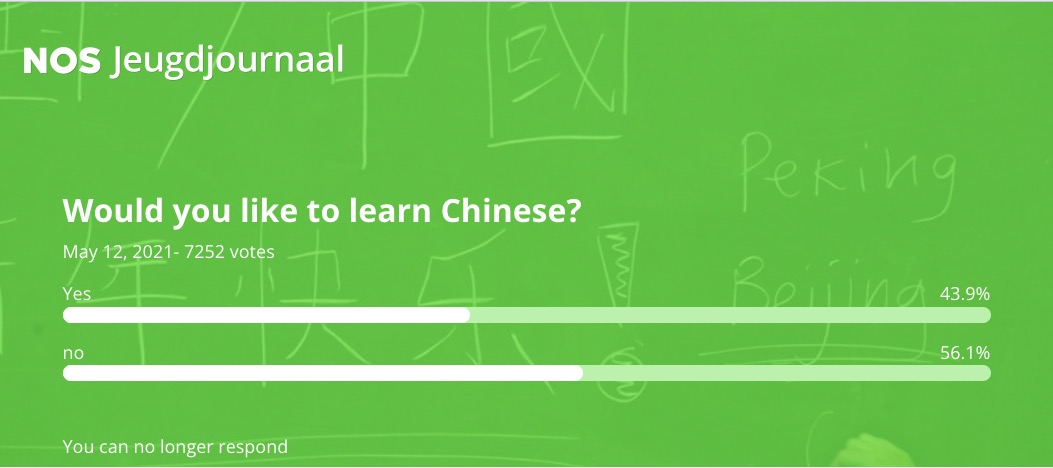

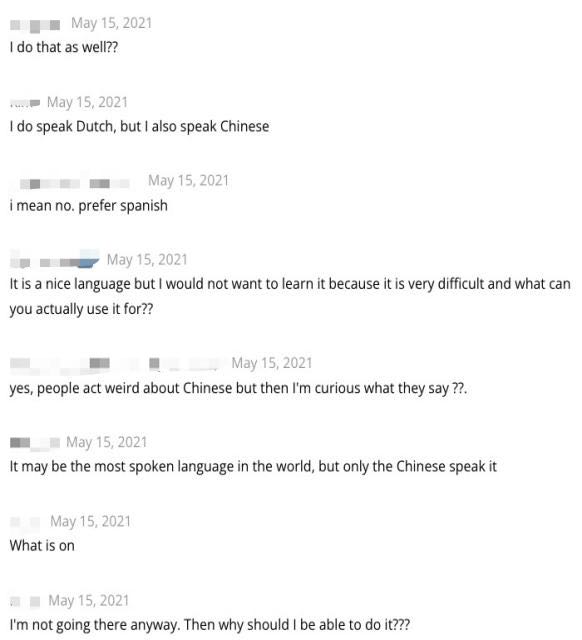

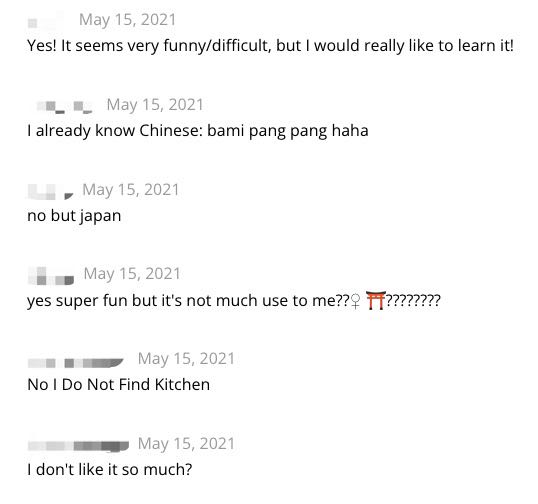

Because a growing number of students are choosing the Chinese language course as an elective course in schools, the Dutch public broadcasting service NOS and its program produced for youngsters, Jeugdjournal, conducted a survey to investigate the levels of young people’s interest in Chinese language learning. 7252 individuals responded, and 43.9% answered favorably to the question of whether they would like to learn Chinese. According to the written responses, the individuals who have a positive attitude toward learning Chinese are because of their curiosity about the Chinese language and culture or because they have someone in their families who is Chinese. Others see English, Spanish, and Japanese as more viable alternatives to foreign languages or, alternatively, do not see the benefits of learning Chinese. The responses show that the complexity of the Chinese language, with its character-based, tonal language, may turn off even the most avid language learners in the Netherlands.

- A survey conducted to investigate the levels of young people’s interest in Chinese language learning by NOS Jeugdjournal (NOS Youth News).

Such a survey reveals that, similar to all other foreign language teaching,

one of the most critical tasks of Chinese language teaching is to arouse learners’

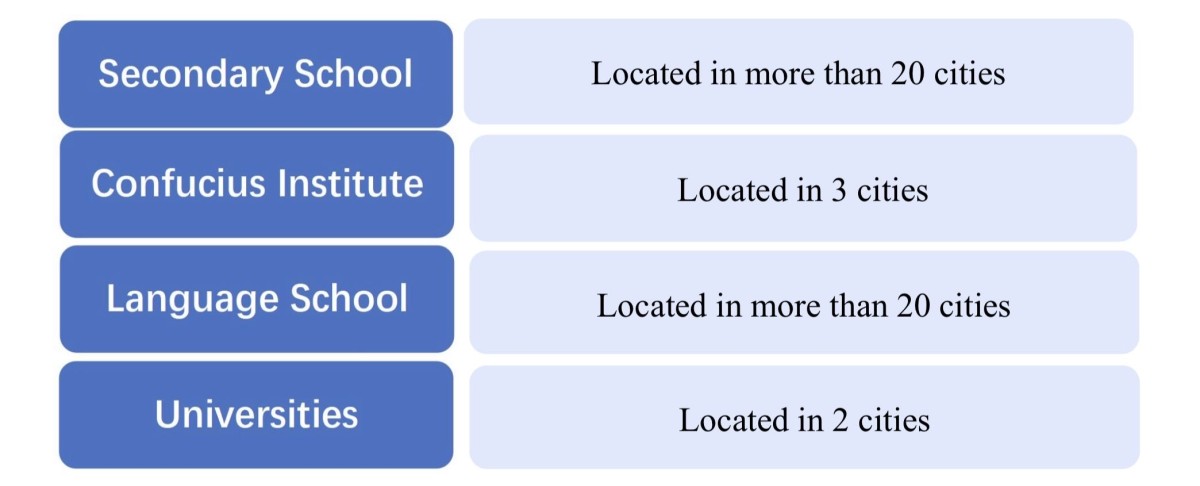

curiosity and intrigue. From the perspective of Chinese foreign language learning, intrigue is to arouse interest in Chinese people; and curiosity to evoke a zest to learn more about the world’s most populous country and culture. In the Netherlands, this curiosity about China and the Chinese language and culture can be evoked in Chinese classrooms in secondary schools, Confucius institutes, language schools, and universities.

- Statistics on the number of Dutch educational institutions offering Chinese language instruction, as of January 2023.

CFL Education in Secondary Schools

The official inclusion of Chinese as part of the Dutch exam system is the result of a pilot started in 2010 in an effort to promote Chinese to further relations between the Netherlands and China. Then, the national network for Chinese teaching was established by Nuffic (https://www.nuffic.nl/en), the Dutch organization for internationalization in education, to promote the quality of Chinese education in secondary schools. In 2019, about 73 out of 648 secondary schools in the Netherlands were members. These schools are spread across a diverse geographical area in the Netherlands, extending from Leeuwarden in the north to Eindhoven in the south. Chinese courses are accessible to students in several cities in the Netherlands, such as Arnhem, Castricum, Delft, Ermelo, Hilversum, Hoorn, Leiden, Wassenaar. Those Dutch urban centers, such as Tilburg, Rotterdam, and the Hague, have more than one school offering Chinese courses.

CFL teachers in secondary schools are generally divided into two profile backgrounds: Dutch-born qualified Chinese language teachers with a university postgraduate degree and native Chinese speakers with a teaching certificate from a Dutch university, such as Leiden University. These Dutch teachers play a pivotal first point-of-contact role for many youngsters whose first active engagement with the Chinese language and culture will be in the Dutch classroom of Chinese. Some of these schools offer Chinese as an elective subject in the upper secondary education of pre-university education. Some offer Chinese as an alternative modern foreign language in the upper years of VWO students who – through this school route – are most likely to go on to university study.

In visiting secondary schools as part of my doctoral research into CFL education in the Netherlands, I noticed that in order to nurture intrigue in language learning, simulating and engaging all the senses in teaching is an essential ingredient. Among some of those best-practice examples are schools that have set aside space to create a quintessentially Chinese spatial environment decorated with interior fixtures and fittings that would be associated with and typically found in China.

- A corner of a Chinese classroom in a Dutch secondary school, captured by photographer Xu Liu.

In teaching and learning Chinese, these items can be drawn upon to literally “bring home” the language and culture to the students. Whether it is the teaching of place, local environment, and geography of China through maps fixed to the wall or the colour spectrum through the array of different colored posters dotted around the room, the classroom space lends itself as a visual aid to teaching. Every time students walk into the classroom, they are exposed to the Chinese language and culture, something that is reinforced time and time again without necessarily featuring it in every lesson plan.

CFL Education in Confucius Institutes

- Logo of a series of Chinese courses provided in Confucius Institutes (Image Source: Groningen Confucius Institute)

Another institution involved in the active promotion of CFL education in the Netherlands is the Confucius Institute. Recruited directly from China from a huge pool of pedagogically well-trained teachers, some of whom have had contact with Dutch culture and the Dutch language, these practitioners are normally native speakers of Chinese with a Master’s degree in CFL teaching. Teachers in the Confucius Institutes have undergone intense professional training to teach Chinese in international settings. These teachers are also equipped with a whole host of skills enabling them to teach in digital environments, most notably hybrid formats engaging Chinese learners simultaneously both in and outside the classroom. Courses at the Confucius Institute are offered to broad target groups, including adults, university students, young adults, and children.

- A learner of Chinese is practicing Chinese calligraphy (Image Source: Groningen Confucius Institute)

CFL Education in Complementary Language Schools

Alongside the state school systems in which certain schools teach Chinese and the Confucius Institutes, another category of schools involved in teaching Chinese is complementary language schools in the Netherlands. These schools were born out of the Dutch-Chinese community’s desire to provide a space for Chinese immigrant children or children of mixed parentage (Chinese-Dutch) to engage with the Chinese language and culture in the Netherlands. Most of these language schools gather on Saturday mornings, often on the premises of mainstream schools. They are community-run schools operating outside the mainstream education system and offering a community-specific curriculum complementary to the mainstream educational content. Understandably, these schools can be found in the urban centers of Amsterdam and Rotterdam with their century-long immigrant communities and well-established Chinatowns. These schools can also be found in Delft, Eindhoven, Leiden, Utrecht, and Zwolle. At the moment of my research, the Stichting Chinees Onderwijs in Nederland [Foundation Chinese Education in the Netherlands] lists 39 Chinese language schools www.chineesonderwijs.nl (accessed January 2023). Some of the larger Chinese language schools have up to 800 students on roll at one time. There is evidence to suggest that an increasing number of non-Chinese, Dutch nationals are seeing language schools as viable options for learning the Chinese language and culture.

CFL Education in Universities

The teaching, learning, and research of the Chinese language and culture can also be seen in the higher education sector in the Netherlands. The research in Chinese is known as sinology in academic circles, which can be traced back to the nineteenth century, as presented in Wilt Idema’s seminal work on Chinese Studies in the Netherlands (2014). The universities of Leiden and Maastricht emerged as powerhouses of teaching and research into Chinese from Dutch perspectives. This legacy lives on in these institutions’ university degree programs, ones that draw on the culture, literature, economy, politics, and society to equip undergraduate and postgraduate students with a solid understanding and awareness of China.

- One of the first phrases to teach in classes of Chinese, captured by photographer Xu Liu.

The teaching of Chinese is not only confined to departments of modern language and culture across the Netherlands, but some universities have their own language centers, opening access to foreign languages to the wider university community. Such language centres, including those at the University of Leiden and Maastricht, deliver practical-orientated language modules where the emphasis of teaching and learning is on grammar, pronunciation, and vocabulary acquisition.

The Challenges and Opportunities of CFL Education in the Netherlands

From secondary schools to universities, from the state sector to the private language schools, this survey reveals the geographical and institutional nature of where Chinese is taught and learned across the Netherlands. CFL education is primarily located in urban areas with pre-existing ties to the immigrant community. Although the Chinese language is widely regarded as one of the world’s toughest languages to learn, improvement in this subject in the Netherlands can be observed. In particular, in the early 2000s, the Dutch government saw the need to promote the country’s knowledge base in China and Chinese to further the relations between the Netherlands and China.

And yet, despite the initial growth, CFL education in the Netherlands is facing considerable challenges. Stakeholders need to find realistic and workable solutions to shore up their position and create a firm footing for growth in numbers in the future. What precisely are these challenges?

The first challenge for CFL teaching is the need to reevaluate and redevelop Chinese teaching and learning materials. Some research suggests that the content of widely used Chinese teaching materials is “outdated” or “lacking authenticity” for the modern-day world. Besides, the standardized materials for CFL learning overseas might not be relevant to Dutch learners’ cultural backgrounds and daily life. In order to retain the curiosity and interest of the learners, efforts need to be put into developing appropriate tools, which include reliable, meaningful resources specifically written for the needs and demands of Dutch learners. In other words, this challenge provides possible solutions regarding further improving the quality of CFL teaching in the Netherlands.

Having an encouraging and collaborative teacher community, for both native-speaker CFL teachers and non-native CFL teachers, to share their teaching experience and exchange their ideas about CFL teaching and learning can be a good way to promote CFL education in the Netherlands. The National Network for Chinese Teaching is a good example. According to data from Nuffic, the Dutch organisation for internationalisation in education, 73 out of 648 schools were signed up to the Chinese teaching network in the pre-pandemic year of 2019. Nevertheless, only three years later, in 2022, this number is down to 25. The loss of 48 schools from the network has a massive impact on the future networking and coordination of Chinese teaching on a Dutch national level, reducing the potential for teaching idea exchange, and curbing knowledge share and information on language learning opportunities in China. Once this type of exchange ceases to exist, it is increasingly difficult to reinstate it. The withdrawal of 48 schools from the network means these schools might make a choice to withdraw the Chinese language and culture course from their curricula. One possible reason behind this might be the great skepticism towards China in the Dutch mainstream media during the pandemic period, which may impose a negative impact on the decision-making of potential learners. The number of learners decreased because of learners’ loss of interest, and schools had to make difficult choices to withdraw Chinese from their curricula. Once lost, be it the routine of Chinese language learning in schools or the regular nurturing of curiosity and intrigue in the language, it is difficult to win back. Thus, sustaining a collaborative network for CFL teachers to exchange teaching ideas in an increasingly difficult, push-back environment is another challenge for CFL teaching.

Tackling these challenges makes CFL practitioners’ work more complicated and gives them certain tensions. However, according to the data from my research, many CFL teachers are still passionate about this profession and willing to contribute to CFL education in the Netherlands. As one of the world’s most spoken languages, learning Chinese as a foreign language can enrich the learner’s life chances and experiences, job prospects, as well as broaden cultural horizons. In addition, through the intricate knowledge of the other’s language, the differences and similarities between cultures and countries can be understood deeper. In this case, a better understanding between the Netherlands and China.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn