Music of bamboo, silk and stone: An introduction to traditional Chinese music

How can the musical history of a huge cultural power, such as China, spanning 3500 years, be summarised in just a few words? Surely, the answer has to be: It is not possible. This endeavour is as unrealistic as trying to reduce down the European musical culture into two sentences. So, instead, I would like to offer some brief reflections about the demands for European listeners who experience traditional Chinese music for the first time. In doing so, I shall address the following questions: Why does this music sound different, sometimes even a bit strange? And are there perhaps some similarities to European music?

The basics: The musical instruments

For the European listener, Chinese music initially sounds somewhat different and strange. This is, of course, primarily due to the sounds generated from foreign instruments, some of which produce a range of sounds that are not so common across Europe.

In China, musical instruments are classified according to the material they are made of. The Chinese system of classification has eight separate categories: metal, stone, earth, leather, silk, calabash, bamboo and wood. This list of materials highlights a remarkable difference to European instruments: silk or bamboo do not feature in European instruments, nor do instruments made of stone and earth (clay).

- The Chinese lute pípa performance © Groningen Confucius Institute

Unlike in most regions of Southeast Asia, in China some of these instruments are traditionally played solo; they are not played in ensembles or orchestras. These instruments have been played for centuries or even millennia. Their music was documented by a special music notation, dating back to the times before Confucius, making the Chinese musical notation the oldest in the world, and these scores provide information about music from over 3000 years ago.

Let’s take a closer look at some of the musical instruments which are still popular today:

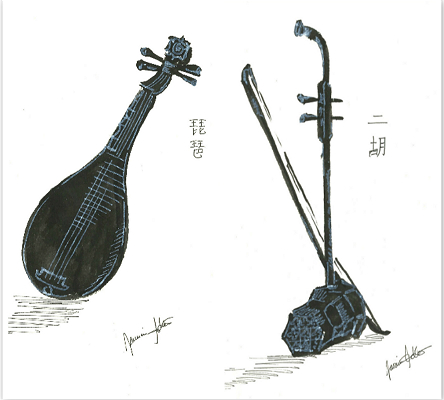

The zithers gǔqín (古琴) and gǔzhēng (古筝), the lute pípa (琵琶), the violin èrhú (二胡) and the dulcimer yángqín (扬琴) are among some of the Chinese string instruments, thus belonging to the silk category. The gǔzhēng is still very popular, enjoying the same sort of status as the guitar or piano in European culture. The sound of the gǔzhēng is reminiscent of a concert harp and is played, just like the pípa, with artificial fingernails, allowing for sounds to be repeated in very quick succession.

- Chinese musical instruments: pípa and èrhú © Jasmin Adler

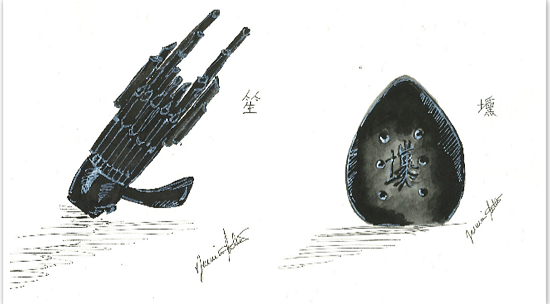

The bamboo flute dízi (笛子), the notched flute xiāo (箫), the clay flute xūn (埙), the shawm suǒnà (唢呐) and the mouth organ shēng (笙) are among some of the members of the Chinese woodwind family. The cucurbit flute húlusī (葫芦丝) and the reed instrument bāwū (巴乌) are more recent additions to this music family of wind instruments. The clay flute xūn was already mentioned 3000 years ago and is the ancestor of ocarinas around the world. The dízi produces a very special sound, as a thin sheet of paper is placed over one of the holes, creating a distorted sound, which is characteristic for this instrument.

- Chinese musical instruments: shēng and xūn © Jasmin Adler

- The cucurbit flute húlusī © Jiang Wei

In orchestras and ensembles, such as the famous Peking Opera, percussive instruments are used, e.g. gongs, cymbals, bells and drums. Of course, classical European instruments are not just popular, but they are really widespread across China today.

The basics: The scales

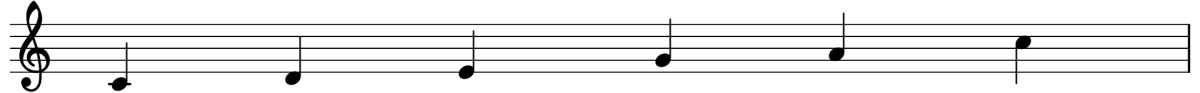

- Dia. C on the musical scale major pentatonic scale © Jasmin Adler

In addition to the appearance and uncommon material of the musical instruments in China, the music performed on these instruments also uses a different tonal scale. In Europe, listeners are used to harmonies of major and minor chords. In the European perception of music, major stands for joy and minor for sadness. Chinese music, however, does not know these harmonies. Chinese music is based on the pentatonic scale, devoid of semitones that creates the difference between major and minor chords. The absence of these chords in Chinese music causes difficulties for European listeners to understand the emotional content of this music. As European listeners are unable to understand the emotions in Chinese music, it does not ‘speak’ or appeal to us as European music does. And yet, the same emotions are present in Chinese music; they are just ‘coded’ in a very different way. Just considering that each of the five tones in the Chinese pentatonic scale possesses its own individual name and special characteristics, it becomes clear that each individual tone in traditional Chinese music has a significant meaning. While European listeners associate minor chords with ‘sad’ emotions, the same works for single tones in Chinese music.

Accessing Chinese music

It is not as difficult as it seems to access Chinese music. A good approach is comparing what appears to be different or strange with aspects which seem familiar.

Outside of pentatonic music, Chinese music also separates the octave into 12 approximate semitones, so the European listener does not hear ‘skewed’ sounds, as can be found, for example, in traditional music from India or the Arab world. Alongside ensemble and vocal music, Chinese music also includes distinctive solo music. Even before the time of Confucius, these purely instrumental pieces were written down in notation. This musical notation, indicating instrument fingering rather than musical pitches, has since found its way as transcriptions into ‘western’ musical scores. For European listeners, solo Chinese instrumental music is easier to access, as for example some compositions for the gǔzhēng or pípa are reminiscent of Baroque preludes.

- The Chinese zither gǔzhēng performance © Groningen Confucius Institute

A visit to a Chinese opera or theatre performance certainly makes for a particularly impressive experience. Here, the musical elements are clearly connected to the emotions of the singers and performers. The Peking Opera is a fairly modern development, but ‘intoxicates’ the senses with a multitude of unusual sounds, loudly accentuating what is happening on stage.

It is also worthwhile to spend some time listening to traditional and modern children’s songs. These remarkable musical forms are often kept simple and are a very useful aid to get used to the pentatonic scales of Chinese melodies.

Please do not consider background music played in Chinese restaurants to be ‘traditional’. This background music has little in common with traditional music from China, except for the ‘typical’ instruments which may feature sporadically in these productions. Anyone searching on the internet for the Chinese instruments listed in this article will not only find numerous videos, but also many CDs with traditional music from China. Fortunately, the internet nowadays is a good resource for traditional Chinese music and the instruments used within.

Source: OctoEast八荒印痕 Youtube channel

The categorization of the instruments gives insight into the many unique sounds which are not to be found in European ensemble or solo traditions. Combined with the importance of a single note or sound and its associated meaning, the music might not ‘speak’ immediately to the western listener. But even without understanding this different language in the notes and sounds, the European listener will be able to enjoy a musical tradition, which is full of variety and among the oldest musical traditions in the world.

Original from the German by Ingo Stoevesandt: Musik aus Bambus, Stein und Seide. Eine Einführung in die traditionelle chinesische Musik in HanBao. Das China-Magazin für Hamburg & Deutschland, eds., Gesellschaft Deutsch-Chinesischer Verständigung (GDCV), Hamburg, Issue 5 (2019), pg. 18-20. Translated and adapted into English by John Goodyear

INFOBOX

Author’s website: Ingo Stoevesandt:

The music of South East Asia

www.musikausasien.de

More information about the music and instruments of South East Asia, sorted according to country, is available on the internet pages of the German ethnomusicologist Ingo Stoevesandt. German speakers can also find an interview about his work.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn