MAGIC CHOPS … or the All-powerful Stamp as a Seal of Approval in China

Be it in the East or the West, the motto “my word is my bond” expresses trust in a business partner. A seal of approval often comes in the form of a contract, signed and sealed with a signature or an official stamp. Today, signet rings and wax seals are very much a thing of the past, characterising a period of legal uncertainty. Perhaps with the exception of official state documents, the use of stamps has experienced a decline in normal day-to-day official business communication, giving way exclusively to a signature, even a digital signature in today’s world.

This is not the case in China. Western businessmen and women are astonished at the immense importance attached to the business stamp in China. The “insignia” appears to possess near magical powers. Not only is the act of placing a stamp on a document celebrated in grand style; the instrument of the stamp itself is protected and guarded like a prized treasure. There is hardly anything that Chinese business leaders fear more than losing their stamp: those losing or misplacing the company’s stamp run the risk of losing power over their entire company. Reports circulate in the Chinese media about employees illegally gaining possession of a company stamp, bringing a company to its knees, even driving it into financial ruin.

- Stamping a document ©Zhang Yancui

Stamp versus signature

Right across Europe, many companies and institutions also have official stamps, yet their importance lies in marketing more than anything else. In normal instances where legal documents are signed, such as contracts, a stamp is of secondary importance. The act of stamping the seal on a legal document does not establish a legally binding relationship between two parties; it is, instead, the declaration of intent of the legal parties, something that is documented by the handwritten signature of respective legal parties.

Once again, this is different in China where signatures have always been mistrusted and attributed a lesser significance and authority in business communication. Signatures can easily be forged; therefore, a personalised stamp has been used for legal documents instead of a signature. This longstanding tradition is probably the reason why there is not the level of concern in China about signature forgery compared to the West. Greater respect is given to official seals and stamps. Forging or imitating stamps is a criminal offence which is not treated as minor misdemeanour, but with the utmost seriousness. Everyone understands why the perpetrator faces a serious punishment.

“Emboss” one’s personal stamp

Everyone used to have one, even multiple personal name stamps which served as a kind of personal identifier, just like the way an ID does today. They often accompanied their owner throughout their life. Depending on the social status and personal worth of their owner, these stamps could be made out of wood, bamboo or simple stone, even from fine, precious or “magical” materials which artists cut by hand. The head of the seal had an artistic design, embedding motifs of a magical and ceremonial nature: images of lions or dragon heads, or scenes from Chinese myths and legends. Owners kept their own stamps safely locked away at home, only removing them from safekeeping to register with the local authorities, to open a bank account or to conclude a contract.

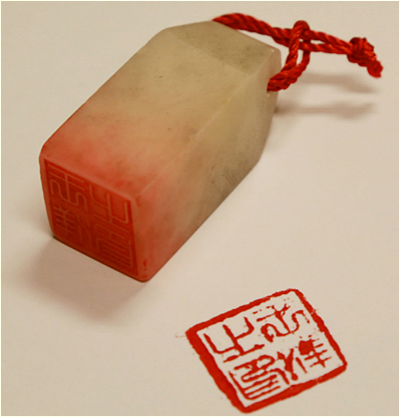

- A personal name stamp ©Wang Yang

Up until relatively recently, in the predigital age, authorities and banks kept an archive of stamps. Printed on transparent paper, they offered a record of stamps of registered customers. A personal stamp placed on a legal document could be quickly and easily verified for its authenticity by placing the copy from the archives over the personal stamp on the document itself. Given that the seals were cut by hand, they were even more secure against forgery than signatures themselves, especially as signatures can vary significantly according to the age of the signatory, his mood, or even physical conditions at the particular time the signature is signed.

Personalised seals of famous people or seals hand cut in workshops by notable stamp cutters have been regarded as antiques for generations. Not only do these stamps fetch high prices; they are also sought-after collectors’ items.

The guardians of the insignia of power

It is not just private individuals who own more than one stamp. Companies, too, have several stamps. Some even have a whole arsenal of seals that are used for a variety of different reasons and purposes, such as financial or contractual matters. In Chinese companies, such stamps are kept securely locked in a strong safe. These stamps would be removed from safe storage by a manager authorised to do so, and then returned back to the safe immediately after use. Each individual stamp is recorded meticulously in a stamp journal log. Some may think this harks back to the past of feudal times, to times when secret communications and documents which were stamped with wax or even customised seal wax. Embossed inside the seal was a further noble counterseal, giving the document official and sovereign approval.

- A company seal ©Liu Yan

The magical aura surrounding the seal as well as the fear of its loss, potentially leading to the demise of a business, are somewhat reminiscent of traditional symbols of power, such as the sceptre and crown in medieval Europe. If these symbols were stolen, then all of the power and glory was transferred to the new holder. In the Shang and Zhou dynasties of ancient China over three-thousand years ago, bronze vessels acted as such symbols. Not only were these vessels used in the court for state ceremonial rituals; they guaranteed power and rule to its holder, to the prince or emperor. If these vessels fell into enemy hands, went missing or were damaged, this loss was synonymous with the loss of power and the demise of the royal house or dynasty. Just like the crown jewels, these bronze symbols of powers were guarded and protected.

We live in rapidly transforming times. And perhaps even the stamp and its associated traditions will soon succumb to globalisation and its customs. But as long as that is not the case, then this rule will always apply when doing business in China: Always pay close attention to the stamps!

Originally published in German by author Gerd Boesken: Magic Chops … oder wie man in China einen Stempel aufdrückt in HanBao. Das China-Magazin für Hamburg & Deutschland, Eds., Gesellschaft Deutsch-Chinesischer Verständigung (GDCV), Hamburg, Issue 2 (2017), pg. 46-47. Translated and adapted into English by John Goodyear

Source: The British Museum Youtube channel

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn